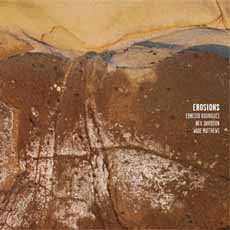

Ernesto Rodrigues

Neil Davidson

Wade Matthews

cs172

Madrid,

July 7th, very, very sunny and over 36º centigrade. Taking refuge in my

studio, which is surprisingly cool, I crank up the Mac and wade through

the spam to discover an e-mail from Ernesto Rodrigues. He and Neil Davidson

are pleased with the music we recorded in trio in March and want to make

a CD of it. Also, Bay-area poet and photographer Mary Petrosky has sent

me a message intriguingly titled “Rocks I’ve Met,” with

some striking photos of… well, rocks.

One is especially beautiful in its erosion. The water that caused it is

no longer visible, but the rock’s surface bears witness to the process.

Of course I’m not looking at the rock, but at a photograph, which

in turn bears witness to the rock. Now, I’m writing about it. Writing

about what? The rock? The erosion? The photo? The process of looking at

the photo? The fact that I’m writing about it? Maybe it’s

the heat, but the whole thing seems to twist and turn around itself like

the curlicue erosion of the stone itself. Rocks I’ve met.

The music Ernesto, Neil and I made in March was also a process, and like

the water long disappeared from between the eroded walls of a dry stone

canyon, it, too, has left its mark.

There is something implacable about how water erodes a canyon, as there

is about the endless sequence of waves with which the ocean assaults and

eventually conquers even the most robust breakwater. At first glance,

water seems to adapt to the form of its container, and yet, over time,

the opposite occurs; it wears away its surroundings, imposing a shape

derived from its own flow. In that process, the stone is scoured and polished,

forced to reveal something of itself that would otherwise have remained

hidden.

Does music do this? Is it as implacable as water? Does it scour? Polish?

Erode? Reveal? If so, what is the subject of this erosion? What bears

witness? What is revealed? Certainly not the grooves of a recording, much

as they may resemble a miniature canyon. Perhaps the CD is like the photo,

bearing witness to the rock but not actually subject to the erosion it

indirectly reflects.

Water is implacable because it has no will. It merely follows physical

laws, though often in very complex ways. Mathematical models of wave behavior,

for example, are enormously elaborate. And in collective improvisation,

the will or intentions of the improvisers interact in ways that vary constantly

between synergy and its exact opposite (a sort of negative synergy in

which the whole is less that the sum of the parts). An improviser can

act with a particular intention, only to find that his act coincides with

that of another in ways that may totally negate his initial intention.

Yet that interaction may just as easily create a new level of meaning

in which the outcome of both acts is somehow even more appropriate than

either of the improvisers expected. So collective improvisation cannot

be the continuous reflection of any given intentionality. Like water,

it flows, and like waves, its exact movement almost inevitably eludes

prediction.

As it flows, water erodes its container, wearing away the hardest of surfaces

to reveal what is beneath. Extending our metaphor, we could say that sound

flows from the actions of musicians, and among listeners. As such, it

erodes both. But it also polishes both, and most of all, it reveals both.

So if this music is the water, then we, the musicians, and you, the listener,

are its container, the bared stones of its canyon. Have we been eroded?

Unquestionably. Polished? No doubt. But what has been revealed?

Wade Matthews

Madrid, July 7, 2010